It’s about balance management to maximizing available grip (then using it)

When most of us learned how to drive on a race track, we were taught to brake in a straight line, ease off the brakes, then turn the steering wheel.

Why?

For new drivers, it’s simpler to manage “braking enough” when we separate the components of corner-entry into their individual pieces. That way, if we interpret (or the instructor shouts) that we need to brake harder, we can do so while not also having to manage car rotation (very much). In fact — we don’t even talk about concepts like car rotation. It’s just too much!

Over time, though, we perceive the car is not at it’s limit in some corners. If we just lift off the brakes and then turn… there is something left on the table. Or, maybe we find that we lift off the brakes and the car won’t turn until we get slow enough or stab at the brakes just a bit.

Eventually, through discussion, research, and instruction, we start experimenting with this trail braking “thing”. But what are we really doing by trail braking?

Hint: it’s not about simply mashing the brakes as hard as we can and then holding on for dear life through turn-in (though sometimes it feels that way).

Using All Available Traction to Brake, Turn, and Accelerate

As we progress as drivers, we learn to utilize all available traction by blending braking, turning, and acceleration together (yeah, yeah — I know that all of those are technically accelerations).

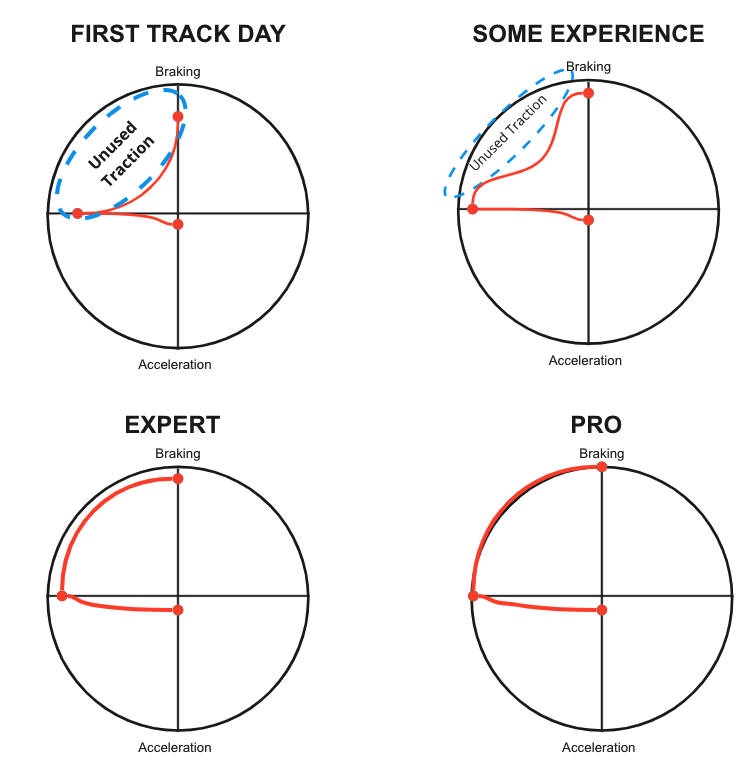

If we consult a g-force chart, we see a progression that looks something like this:

Over time, the “Unused Traction” area shrinks until we’re (hopefully) looking something like “Expert” in a lot of corners… I’m still working on that part. A lot.

But regardless of where you or I am at, we’re looking for ways to make our to get closer and closer to “the limit”, which will show up on our data devices as tracing nice arcs around the edges of our g-force graph. What do we need to consider?

One major thing is: car balance management.

Managing Car Balance & Maximizing Grip

We have two basic tools at our disposal to manage the car’s balance fore and aft: they’re the gas and brake pedals.

By depressing the gas, slightly or fully, we shift weight to the rear of the car. By lifting off the gas, we incrementally shift weight back to neutral — or, if we lift off-gas sharply, we actually shift the weight more forward.

Likewise, with the brakes, we can depress them lightly, firmly, to the floor, and at varying rates of pressure increase/decrease.

Think of them as volume knobs — you can quickly “jump” to a 7 on the scale, hold it there for a second, then quickly dial back to 0. Alternatively, you can gradually build to an 8 and immediately begin dialing back to 0.

The options are endless! This is why braking is so difficult.

We determine how much weight is transferred fore and aft by how we depress and release the pedals.

So what does this mean, in terms of why we trail brake?

Trail braking keeps more weight on the front of the car than if we were to be completely off of the brake pedal or on the gas. This, depending on a massive number of variables in the car, corner, and conditions, can give us more grip to turn with than if we were completely off of the brakes!

It’s counter-intuitive, maybe, but it’s true. Even though a tire has only so much grip to give, and in a controlled setting we would want to use 100% of it for turning while in a corner… we actually only need the tire to be used for 100% turning in certain portions of certain corners!

A Practical Example — The ‘Attitudes’ at UMC

The Attitudes are a set of left-right-left corners that start at the crest of a reasonably sharp incline.

As we go to the brakes and prepare to turn-in, we’re approaching the crest of the hill — what do we know about cresting hills?

- The weight of the car is already biased to the rear by going uphill, making the front tires somewhat “lighter” than normal

- As we crest, the front tires are temporarily “lighter”, as we’re going somewhere around 60+mph — we don’t “catch air”, but the car weight is transitioning

- As we begin the downhill segment, the weight bias is now to the front

So, what does this mean, in terms of trail braking?

- We begin turn-in as we are almost to the crest of the hill, meaning our car’s weight balance is biased to the rear

- As we ease off the brakes and begin turn-in, we need to keep just a bit of pressure on the brakes so that the front tires don’t get as “light”

- By using the brakes to keep some more weight on the front tires than they’d normally have when going over a hill, we increase the grip of the front tires

- By increasing our front tires’ grip, we can carry more speed!

Bonus: throttle application

- As we crest and the car has turned left, we are off of both pedals — the car is now shifting weight forward due to the slope of the hill

- At some point just after the crest, we need to turn right.

- At about the same time, we can (and should) begin depressing the gas pedal

- By doing this at the right time… we have increased the rear grip and can go “hammer down” on the gas! We don’t need as much front grip at this point.

[A few] Patterns of Brake Utilization

Maybe you’ve driven UMC, maybe not, but hopefully this has given you something to think about when you’re attempting to maximize entry-speed on that corner you always seem to lose time in.

Start thinking about what you’re doing with the brake pedal (and when), then start comparing notes/data/video with a driver who seems to do that corner better than you.

What type of braking can be utilized? Here are just a few:

- A brake “brush” that is slight and subtle to “set the nose down” a bit?

- A brake “jab” or “bump” to do something similar (but in a shorter amount of distance/time) — these are rare and often used in combination with keeping the throttle pinned (left-foot braking required)

- Is it a hard and constant brake pressure until trailing off? So, braking over quite a bit of distance — often used going from long straightaways to hairpins

- How quickly do you build pressure? Can you build pressure more quickly so you can start trailing-off the brakes more quickly (and potentially braking later)

- Do you even have to hold constant brake pressure, or can you start trailing off the brakes as soon as you get to your maximum braking pressure? Most often in moderate corners at the end of short straights.

- Do you need to drag that 10% brake pressure for longer to keep the front tires from beginning to understeer? And, especially for you FWD drivers, keep the back-end light and rotating around.

- Does braking need to happen before or after turn-in? There are a surprising number of corners where you can turn-in under throttle, then brake in a straight line and trail-off as you turn some more.

Bonus: How about steering?

- Do you need to quickly “flick” the wheel to a certain angle, or is it a gradual turn as you get deeper into a corner?

- Are you able to use a single steering-wheel motion, or do you have to turn-in some, then turn-in more?

- Are you able to start unwinding the wheel shortly after apex? If not, are you at least able to roll to full-throttle just before or after apex?

How to Start Practicing Trail Braking

A simple and safe way to approach trail braking goes something like this:

- Choose one corner that has a healthy amount of runoff (preferably paved). Most likely, this will be a high-to-low/medium speed corner (like a hairpin or moderate-speed sweeper).

- Move your braking point to be about 1/2 of a number board (say… 50 feet) earlier

- Brake just a little bit lighter so that you can get down to your normal corner-entry speed, but over a longer distance (brake lighter, but for a bit longer)

- When you approach the turn-in point, keep your foot barely resting on the brake pedal. Leave it there until it’s time to throttle-up — either at or just before the apex

- Drive the rest of the corner normally

- Once you’re comfortable playing with the brake pedal pressure after turn-in, start moving your brake marker back to it’s normal place.

- When that is comfortable, you may then try making it just a touch later (we’re talking about within 10 feet of your normal point) and rely on a bit more brake pressure post turn-in.

- Have fun!

Final Thoughts

Once you’re aware of what the car weight is doing in a corner and where you tend to “run out of grip”, you can start considering your options to add or remove weight to those tires through your inputs.

As you gain confidence that you’re getting everything from the car, then start tinkering with setup. Setup is a whole thing on it’s own, of course, and remember that what works for one driver may not work for you! Remember: change one thing at a time.

Lastly — the point of trail braking is to use the brakes to slow the car while also adjusting it’s balance in the corner-entry and mid-corner phases. You’ll know you’re on the right track when you’re able to consistently apply maximum brake pressure early in the corner, then smoothly release that pressure without having to re-apply the brakes any harder.