A few months ago, I had the opportunity to sit right-seat for a talented young driver. The task for the session was to evaluate where he was at, skill-wise (and otherwise) and pass feedback along to our Chief Driving Instructor. This driver’s goal is to get a race license as soon as possible and his father’s goal is to have his son crowned the next F1 candidate.

Let’s just say that I’m glad I didn’t have to duck “dad” on this particular day.

I was very happy, actually, to have a chance to sit with this driver for a bit. Let’s call this driver… Bill.

Bill had been coming most of the events for the year and had gotten on my radar for a few notable exploits:

- Having an overbearing father with delusions of grandeur for both himself and his son

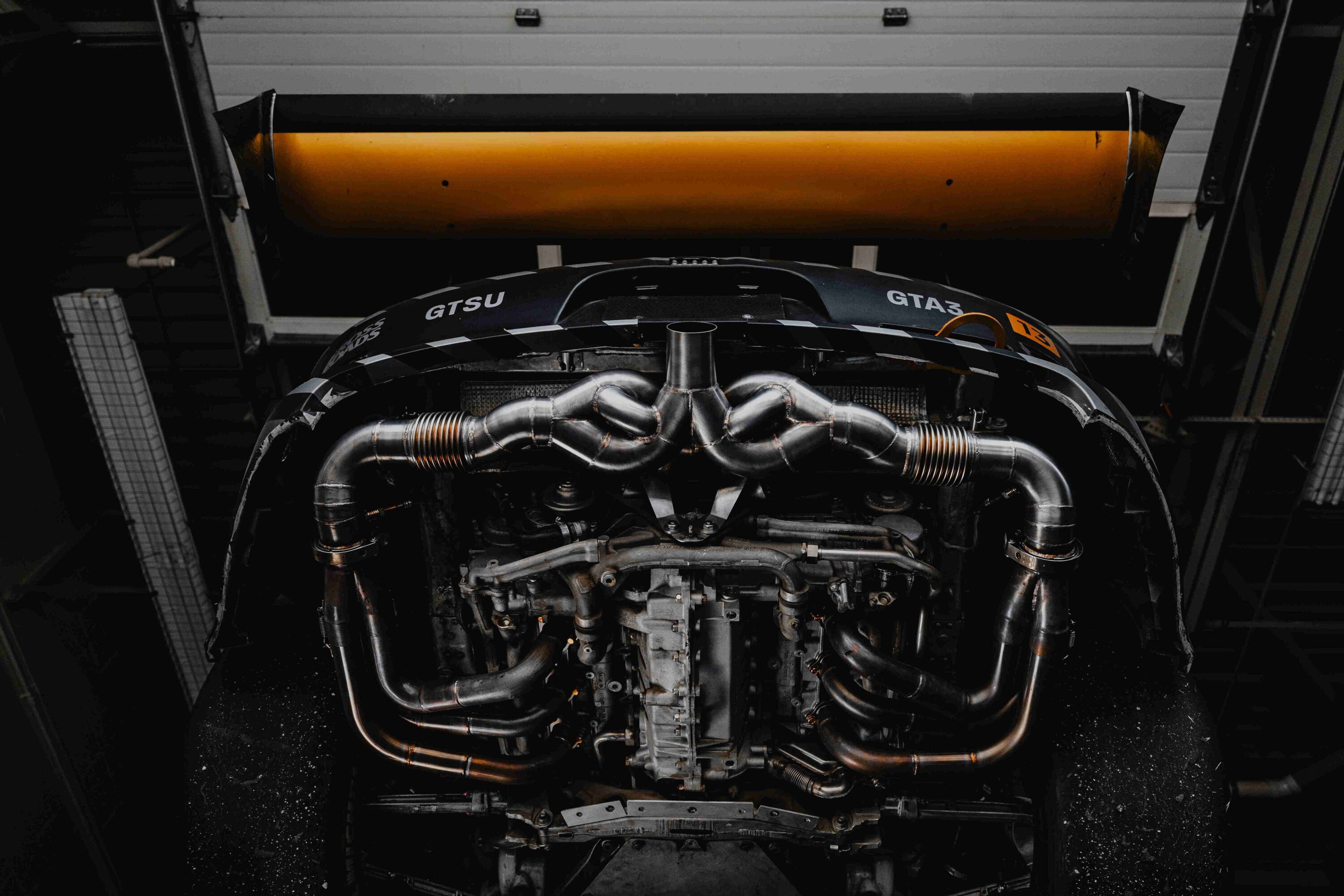

- Wadding-up a Porsche Cup Car

- Spending time with a pro driver who gave a talk and set reference laps for drivers who shelled out a few hundred bucks

- Listening to good sense and subjugating himself to driving a Spec Boxster (I think this has more to do with dad listening to good sense — the kid is just happy to drive!)

So not all bad, but a few things to manage on top of the whole “driving thing”.

I’ll come across drivers (and parents) like this on somewhat regular basis — they’re highly motivated and, to one degree or another, give off an air of ‘moving through’ any given licensing program as a mere formality on their path to greatness. We’re just the local car club, not a pro-am race series; what could such aspirational drivers learn here?

I digress, but want to set the stage: I finally had a few precious minutes alone with Bill.

I was chatting with Bill a bit, asking him what race class he was planning on competing in, asking who else he’d had instruct him, and so on — trying to build a relationship. I could tell that Bill was nervous as he spoke about things and I hope my inquiries were easing his nerves, rather than compounding them. As I was complimenting Bill on the build quality of his freshly-minted Spec Boxster, I noticed something:

The safety pin was in his fire suppression system handle. With this pin in-place, the fire suppression system could not be activated by anyone: either by pulling either of the remote cables or the actual handle itself.

The bottle was mounted on the passenger floor, with my calves wedged haphazardly around it (passengers get short-shrift, sometimes), well out of reach of any driver. Out of my reach, too, for that matter.

There were two remote-pull cables attached: one running to the dashboard for the driver, the other running outside for a safety worker to easily access from outside the vehicle.

Gesturing to the fire bottle, I say “I appreciate you leaving the pin in so I don’t kick the handle, but I’m going to pull the pin, OK? I don’t think we’ll need it, but better safe than sorry.”

Bill looked over to me, glanced down at the floor, then confidently patted the T-handle mounted to his dashboard, saying “I pull the cable up here.”

After a short explanation of why pulling the handle would do nothing, given the presence of the safety pin, I thought that I had already helped this young driver out, even before we had hit the track! Not so. Bill cocked his head, raising his hands in a gesture of what I’m sure he thought was being matter-of-fact, and said “I don’t know about all that, my shop takes care of the car.”

I was dumbstruck. As I loosened my belts and origamied myself low enough in the car to pull the pin (and not bump the handle), I realized that this was a lost cause for the moment. Pontificating over how this driver was subjecting himself to a very real risk of injury and possibly worse by remaining ignorant of his vehicle would gain nothing, most likely causing him to write-off any advice I was about to share that would help him attain his driving goals.

The only further action I took on the matter was to mention the state of the safety pin to the crew chief before we rolled out, in a similar face-saving manner. Who knows: maybe the pin was left in on purpose or maybe it was forgotten in the hustle — there have been a few times that I have forgotten, myself.

On to the driving

The session went well enough — Bill was driving fairly well. Not race license material, yet, but showed promise. The only coaching I determined to be effective in the moment was providing guidance on when and if to try for passes. Bill was driving well enough to close on faster cars in the twisties, but not quite experienced enough to time when he would close on the car ahead such that there was half a chance to get side-by-side before the more powerful cars would put the hammer down and leave us behind.

This situation is common: faster driver, slower car. You work your tail off to reel in a car, only to come to the long straightaway and see all of your progress vanish before your eyes. I was pleased to see this as Bill’s #1 opportunity, really — it’s a situation that would encourage good habits and punish bad ones.

In our debrief, I explained this opportunity to Bill, as well as a tendency to send the car deeply into braking zones, treating the car like it had twice the power. But Bill only cared about one thing:

“So am I ready for my race license?”

The answer was a kindly “not yet”. I did, however, send my recommendation to the Licensing Director that Bill be granted a Time Trial license: the goal here being to place Bill in situations where he would have to hone his craft in order to make passes happen — he wouldn’t be able to rely on his car’s capabilities. In fact, as he got faster, he’d find himself in more situations where he was a faster driver, but had no chance of chasing down the car ahead without some serious strategy.

Time will tell if Bill figures some of these things out. I’m hopeful that he will.

The Takeaway

When we go to the track, we’re typically thinking about the fun part: going fast and making passes. Things like fire systems, that nagging electrical issue, and spending a couple of sessions to fine-tune the alignment can quickly go by the wayside or be identified as issues to be solved by more capable hands. Even more, if you buy a race car, it can be a bit overwhelming to figure out all of the quirks and nuances when you’re now ‘supposed to be fast’, right?

For some drivers, the solution comes in the form of stabling your car with a shop who does trackside support. Maybe you go all-in, maybe you do a-la-carte (I’ve done both), but you spend good money to have a race shop answer your questions, set up your car, fix it in a pinch, or anything else that comes to mind: for the right price, nearly anything is possible.

There’s nothing wrong with this solution, particularly when the price tag of all the spare parts, tools, and equipment start to skyrocket. Mistakes become costly and you want to focus on the fun part: driving. That said, I’ll consistently recommend to drivers to do a few things when they get into the sport:

- Murphy’s Law isn’t proven when it’s convenient to you. Murphy’s Law says that “if anything bad can happen, it will”. And that means the one time you leave your fire system pin in by accident or because it’s ‘just a warm-up session’… bad things will happen. Wear your suit, arm your fire system — every time.

- Work on your own car. By putting a wrench on the thing, you’ll naturally accumulate knowledge and tools. There are many benefits to this, which I’ll go into depth on in a later article, but in Bill’s case, it’d make him more familiar with how things actually worked on his car. Change the oil, rotate your own tires, take your own air pressures… something!

- Ask how things work. This may seem silly or obvious, but any shop worth your money will answer your questions and educate you on the basics of how your car works, why certain maintenance is needed, and what to adjust in order to change it’s handling or performance characteristics. This also has more benefits than listed, but the two main ones are your own knowledge and some insurance against you being taken advantage of.

- Don’t be ashamed of saying “I don’t know”, or “Dang, good catch”. We all want to be perceived as competent ‘car people’, right? I can’t count the number of times that a buddy flagged me down for trying to drive off with a notebook or something stupid on my trunk, or the things I’ve learned from people who I remember teaching the very basics to. Be approachable and humble and your fellow drivers will have your back; be arrogant and we’ll assume you already know… or leave you to your fate because you’re a jerk.

- Don’t let your ambitions get in the way of being present in the moment. I mentioned how some drivers come to the clubs I race and instruct with as a means to an end. That’s foolish. There’s plenty to learn from most groups you’ll drive with and if you weren’t in a kart as a kid… F1 isn’t in the cards for you.

- Don’t be “that dad/mom”. The keepers of the keys will groan when they see you coming and instructors will find ways to be too busy to work with your kid.

Bill wasn’t arrogant or rude, but is certainly missing out on some opportunities to learn as he goes along his path to… whatever he (or his dad) are aiming for. You don’t want to find yourself in a situation where you are helpless without a support crew, because at best you’re going to spend more money than you need to; at worst, it could cost you your life.